Typography, Design and Activism

TYPO Berlin

An Interview with Iranian Graphic Designer Golnar Kat Rahmani

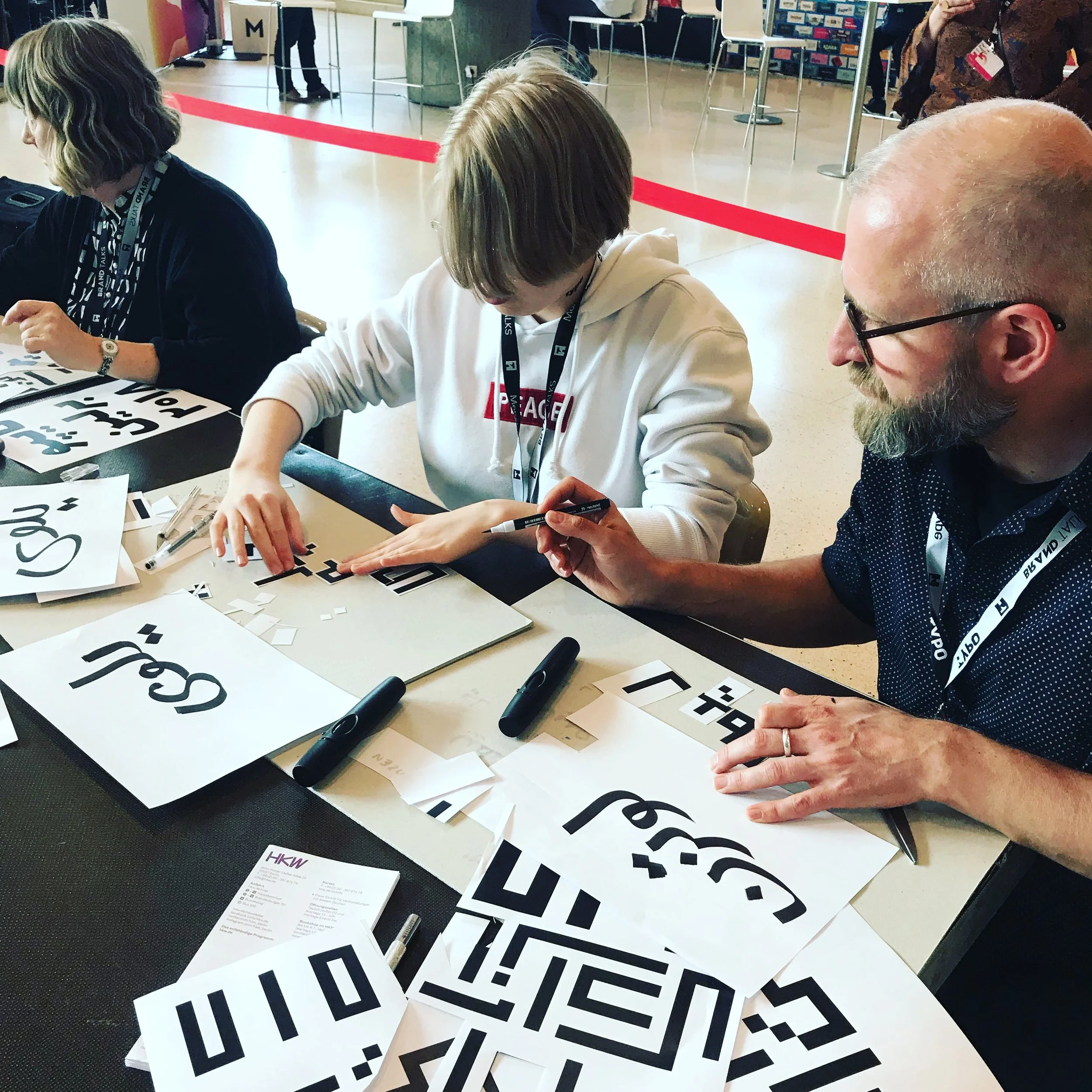

Golnar Kat Rahmani is currently based in Berlin and known for her work in the field of Arabic and Persian typography. Her aim is to remove the negative and political perceptions of Arabic type – to eliminate the prejudices and/or break the stereotypes that are attached to it. In a way, she uses her skills to activate people and create a world with less judgement and more understanding. I talked to Golnar Kat in May 2018 at TYPO Berlin where she led a silkscreen printing workshop, called Type & Politics, on this subject.

I’d say, you are not only a designer but also an activist who tries to bring people closer together. Where does your activism come from?

I’m very interested in politics because every political decision has an impact on a person’s life, especially in a country like Iran. As Iranians, our everyday lives are captured by politics. I might live in Germany now and can travel anywhere, but it surely affects my life that Donald Trump just withdrew from the Iranian nuclear deal. I have family and friends in Iran.

What exactly do you do in terms of design and activism?

There are different projects I curate and/or I’m part of. The workshop I do for TYPO Berlin is about type and politics. It is about how type gets politicised. Then, I recently worked on a project called Nicht ohne meinen Glauben! [Not without my faith! in English], which calls for action against anti-Muslim racism and for intersectional justice. I was also affiliated with the blog Encounters about refugees; it is a collaborative multilingual media project by Engaged Anthropology.

You’ve just mentioned that the workshop is about how type gets politicised. Please elaborate on this…

Our main source of information is the media that chiefly disseminate sad or negative news about the Arab world, also Iran and Afghanistan, as well as about Islamophobia that is very much present. As a consequence of that, the Arabic and Persian type evoke a certain association in people when they encounter them. So the type itself is judged. This affects not only the type but also the people using it. And it doesn’t have to be like that; the type itself should not be political or make people scared or insecure. Therefore, during the workshop, I talk about our unconscious biases towards the written form of a language.

Have you ever experienced unconscious biases yourself?

Yes, this has happened to me in Berlin. Even if I’m not the typical looking Muslim girl, I can see that people feel different when I carry a book written in Arabic or Persian. First, I thought it happened because of my look, as they can’t really relate the type to my image, but then I realised it was more about the type itself. I tried it again and again, and there were always these feelings… But if you think about it, the text could be in English, Indonesian, or any other language really.

What are your aims with your workshop?

I want to show how the Arabic (and Persian) type can be used in different contexts such as the arts, culture, love, etc. Basically in any context but politics. So I had the idea of developing a workshop around it to tell the history and the other aspects of this type. In the workshop, we learn what Arabic type is, then we briefly practise Arabic typography, and after that we use the silkscreen print technique to bring our designs out. The participants make a connection with the type, a connection that is not loaded with prejudices. Hopefully, while they are experimenting with it, they become more curious about it and their perception changes a bit. So the next time when they see this type, the new memories made during the workshop come across their mind and not that black and white graphics that ISIS uses. They won’t be limited by the information repeated in the news but remember how great that evening was when they were learning about Arabic type.

Do you think you can respond to all the news the media generate?

Of course not, and I don’t want to. I have no intention to be that one person against the system or something like that. If a media outlet has an agenda, I can’t really change that on my own. I do what I can do best: I can create and spread the knowledge I have. The world is out there, so we have to produce material people can have access to if they want to see something different. I know many people support the cause so I do believe we can reach a wider audience. Of course, a lot of things are happening in the world right now, but even if this is just a small attempt, I go for it. At the end of the day, it’s not about creating a new world but helping people become more comfortable with this type, in the world we live in.

How much does the composition of the group influence your approach when organising/leading a workshop?

Very much so, I always adjust my approach to them. For example, I expect that the participants at TYPO Berlin will be comprised of people working in the field so they are probably not judgemental towards the type but more curious about it.

TYPO Berlin 2018 | Type & Politics workshop | Kufi Typeface

Going back to your everyday work a bit. What kinds of projects are you usually commissioned to do?

Clients normally contact me if the project is related to cultural, social, political issues, or they need someone who can work with Arabic and Persian type. I’m open to both kinds. Right now I mainly focus on typographic designs including both Roman and Arabic typefaces. It’s indeed complex and challenging work, as they are very different in their shape/design, and they also differ in their cultural background to a large degree. If you want to place them together, you have to have harmony. My job is to create that harmony.

Please explain it in more detail.

The visual communication in each culture is so different: what you find good or bad. You can’t display them in the same context just like that. For example, a great design from Iran might not be considered great here [in Western Europe] and vice versa.

Featured image: Mart-Stam-Stiftung | KH Berlin Weißensee | Poster Design