Brain Bar Edition: ‘How May I Help?’

An Interview with Luc van Hoeckel

Visitors and guests from all over the world debated futures at Brain Bar Budapest in 2016. On the second day of the event, we sat down with Dutch designer Luc van Hoeckel, who gave an inspirational talk on social design when presenting their project realised in Africa, to discuss the purpose of design.

First of all, congrats! The work you’re doing is remarkable and inspirational to us all.

Thank you.

Luc van Hoeckel & Pim van Baarsen

One of the greatest things about your projects is that you work with local people and grassroots organisations. This can be quite difficult sometimes due to the fact that you need to earn their trust first. This applies to your project carried out at hospitals in Malawi as well. How did you approach the locals with this project?

The question is how we can involve the end-users in our projects. Concerning this particular project, the end-users were the hospitals we were about to work with, and we got the locals trusted by involving them in the project. We didn’t know anything about hospital equipment, since we are designers and researchers, so we gave them the role of designers and experts, and we asked them about the nature of the project.

Thanks to this approach, we found interesting and relevant facts that we couldn’t have been able to find ourselves. They said, for instance, that they didn’t need electric beds there in Africa because the electric power system is unstable and power cuts occur frequently. They added that the beds imported from India were good and enough for one person to lie on, however, in Africa it is normal to have the entire family sitting and lying on the bed.

How much research did you do besides getting these valuable pieces of information?

We got in touch with 5 hospitals to involve them in the project. Some of which were located in more developed cities while others were in rural areas. We conducted dozens of interviews and did weeks of research in every department to see what they needed. We talked to doctors and other medical employees, and patients as well. In addition to that, we approached the staff that buys the medical equipment.

What kind of tools and pieces of equipment did you design?

We made a total collection of 10 pieces of hospital equipment. Before we came to Malawi, we didn’t know what kind of equipment we were going to make. We didn’t know what their needs were that is why it was very important to work together with the doctors, nurses and patients. We looked into what kind of tools and equipment they needed, and then we finally designed 10 products together. For instance, products needed in the operating theatre and in the wards (e.g. trolleys).

It’s great that you managed to produce 10 products for these hospitals in need. I’m wondering, though, whether this process/production is sustainable or not.

We didn’t only start the production there, but also applied a kind of warranty programme. So if something needs to fix in six-month time, they can just return them to the company and get them repaired. This step is extremely important, since imported hospital equipment from Asia, America or Europe have no warranty at all.

It seems you work in lots of places. Where is your studio Super Local based?

Our studio is based in the Netherlands but we always prefer field research over desk research. It’s really important to see and experience the place on our own and find out what is needed there — to get an understanding of the complexity of a problem. We want to work with them instead of for them, to become equal partners, and solve problems together.

Isn’t it dangerous sometimes?

In Uganda, my colleague and I got malaria, which was quite achy. Other than that nothing really bad has happened to us until now. People are always kind and give us a safe place to sleep.

You studied design to be an industrial designer. When and why did you turn to social design?

To be honest, at a certain point I was a little bit tired of design, the “traditional design” that is taught in school. I didn’t want to design another chair, lamp, desk or whatever. In the Netherlands we have and/or can make everything so for me there was no real challenge, while in developing countries you have to use your creativity to make things happen. I wanted to use my creativity to push the world forward. I turned to social design because I find the conditions in which so many people are forced to live to be unfair and unnecessary.

Do you work together with other Dutch initiatives/organisations/companies focusing on developmental issues?

Yes, we do. Sometimes we receive an assignment from a company based in the destination country, sometimes we work for NGOs in another country. For example, even if our first project called Singe Spark didn’t work out, we sold the concept to a company that now produces lots of starter kits in Uganda and Kenya. We worked with SPARK ONLINE that is an NGO, we did a project with the starter kits in Kosovo.

Money is usually the biggest issue concerning carrying out projects. How do you get funded?

This totally depends on the project. Most of our projects are funded by the client we work with, but sometimes it also happens that we invest our money. In Nepal, for instance, we are working on a waste project. We went there once and could see that there was a great mess everywhere in Kathmandu so we thought we should do something about it, and therefore we invested our own money to launch a project. That was the case with my graduation project in Uganda as well.

So it has worked out great so far…

Yes, but with ups and downs, of course.

Please give us more details on the project done in Nepal.

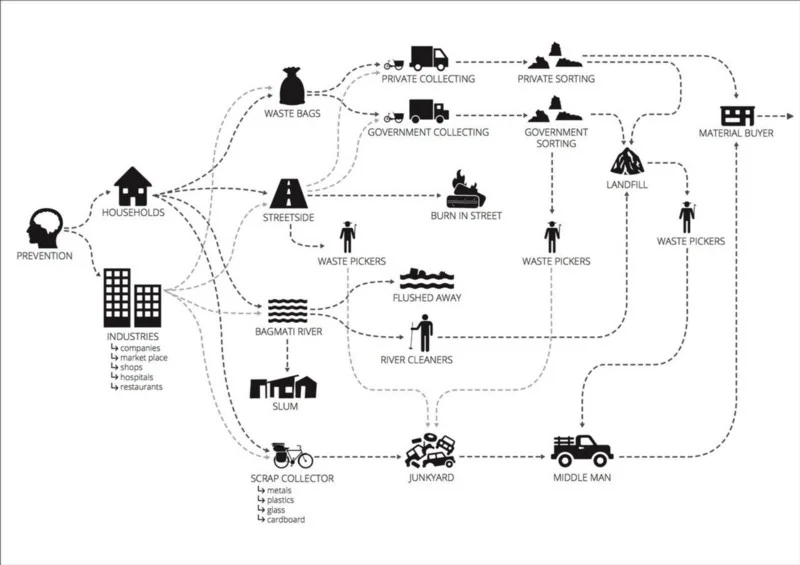

Waste management does not really exist in Kathmandu. If people are lucky, their waste is collected once a week or every other week. They can either throw the rubbish outside or in the river, or burn it. We were shocked when we saw this. Unfortunately, the government is also in a mess so it is not their priority to deal with this issue, moreover, people need to survive day by day so they put all kinds of waste into one bag instead of collecting them separately. Since this issue has a big impact on health, we tried to come up with an idea to solve this problem. We created a system that is targeted at individuals. If they separate their waste, they can earn points, and they can exchange those for phone credits or get discounts at certain shops. If private companies collect waste separately, they can sell the plastic, and the organic waste to local farmers so they can use it as organic fertiliser. This is what we are working on right now. We found a partner, but, due to the earthquake that occurred in April 2015, we are on pause.

Do you collaborate with other designers — using a platform maybe?

We don’t really have a platform. Of course, we’re on Facebook and Twitter but that’s it. Nonetheless, we often work with our friend Dave Hakkens, the founder of Phonebloks and are currently collaborating with four other designers on a glass-recycling project in Zanzibar.

Pim (Pim van Baarsen, co-founder of Super Local) and you also studied at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Please tell us about your university years there.

The first year is completely free, and we have 8 different design directions. In the second year you need to choose one of them. I decided on taking the one called Man & Living, which is more about interior design. After one year I got bored so I continued my studies taking courses within the framework of Man & Activity, which is mainly about product design. During that time we focused more on smaller issues to make life easier. Basically, I designed gadgets. I had the feeling that first I was creating a problem, and then finding a solution to it. So I asked myself: Am I really solving problems or just making life easier for the wealthy? That was the moment I decided to dive into the world of social design.

How do you see the field design in general?

If you look at the world, you’ll see that traditional design is targeted at only 10 per cent of the world population because they are the ones who can afford to buy this great variety of products developed. What about the other 90 per cent? There are so many upcoming countries that need products and services that make a difference and improve the quality of life. It’s the biggest part of the world! You see those new trends like social design, which I also welcome. What is difficult you need to be there to work, you cannot do it from home. I do hope that more designers will step on the path of social design and address issues in developing countries.